The Haiku project site: haiku-os.org

Source code: haiku

The Haiku operating system is a rare example of how enthusiasm and a love for elegant engineering can breathe new life into an idea that might otherwise have faded into history. Its roots go back to the mid-1990s — a time when personal computers were only beginning to realize that a graphical interface could be more than just a convenient shell; it could be an integral part of the system’s very architecture.

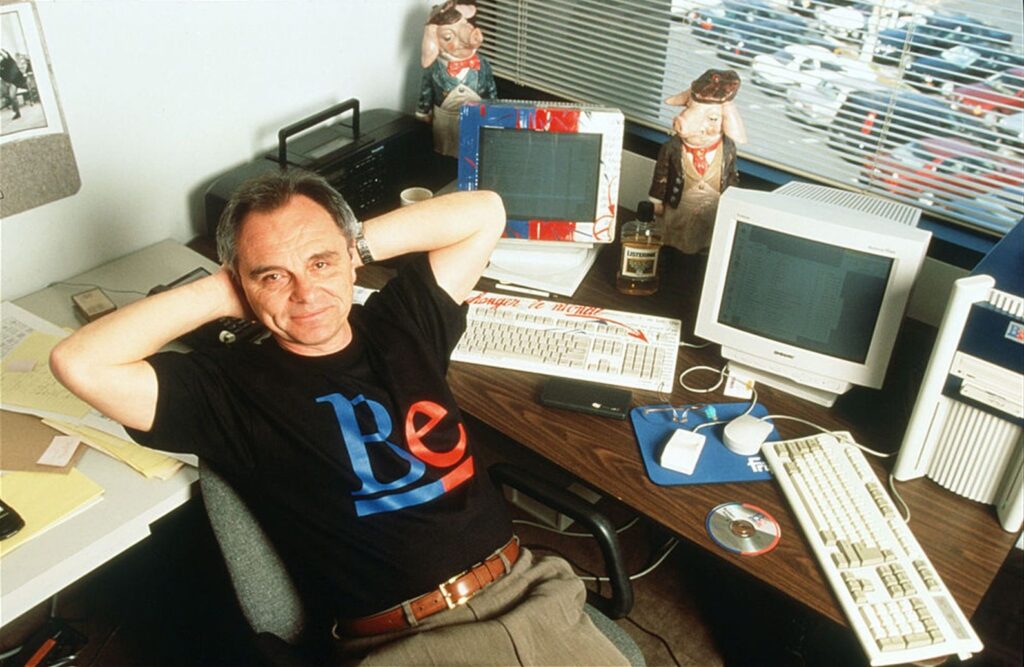

The story of Haiku is inseparable from that of BeOS, an operating system created by „Be, Inc.”, led by former „Apple” executive Jean-Louis Gassée. Founded in 1990, „Be, Inc.” set itself a near-romantic goal: to build a next-generation OS free from the legacy of old platforms. BeOS was written from scratch — with no reliance on MS-DOS, UNIX, or Mac OS — and was designed around multimedia, multithreading, and instant responsiveness. Yet since most „Be, Inc.” engineers came from „Apple”, the system inevitably bore a resemblance to MacOS Classic. 🙂

BeOS was revolutionary in many ways. It featured a fully journaled file system — BFS (Be File System) — supporting live indexing of arbitrary file attributes. Essentially, the filesystem worked as an integrated database. A user could instantly search for all documents whose “Author” field contained “Alexey Burshtein,” and the results appeared almost instantly. Searching a 40-GB hard drive took about two seconds — back in the late 1990s! The system supported symmetric multiprocessing as early as 1996, had a 50-millisecond scheduler granularity, a built-in 64-bit audio stack, and a journaling filesystem at a time when Linux was still using ext2 and Windows 95 had no idea what crash recovery even was.

I was a university student then, and in December 1999 I installed BeOS 4.5.2 for the first time. The experience completely transformed my understanding of what a computer could be. The system booted in 12 seconds — whereas Windows took 12 seconds just to begin its preliminary startup routine. BeOS responded instantly to user input; its applications were only a few megabytes in size yet fully multithreaded by design — every GUI application handled its interface in a separate thread. Even today, a quarter century later, I remember setting up my Epson Stylus Color 600 printer in five minutes — four of which I spent in disbelief, wondering if it really could be that simple. BeOS wasn’t just fast — it was honest. Programs did exactly what they promised and wasted not a single CPU cycle.

Alas, commercial success never came. BeOS suffered from a lack of drivers, hardware vendor support, and market inertia. In 2001, drained and weary from competition, „Be, Inc.” was sold to „Palm”, and its source code disappeared into corporate archives. It seemed the story had ended.

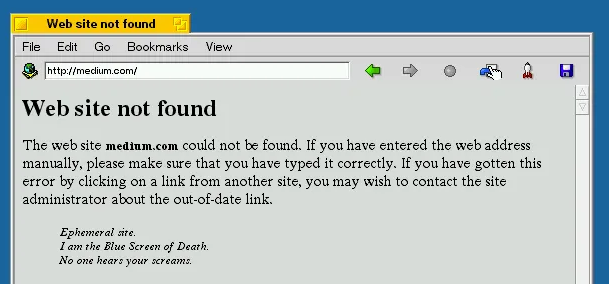

But the idea proved more resilient than anyone expected. In 2002, a group of enthusiasts launched OpenBeOS, later renamed Haiku — in honor of the short Japanese poems that BeOS’s default browser, NetPositive, displayed alongside its error messages. The goal was ambitious: to build an open-source operating system from scratch, binary-compatible with BeOS but updated with modern drivers, network stacks, and architecture.

More than twenty years have passed since then, and Haiku lives on. It evolves slowly but steadily, preserving its founding philosophy — minimalism, responsiveness, and respect for the user. It’s not “just another UNIX-like system”; in fact, Haiku isn’t part of GNU and isn’t based on the Linux kernel at all. Haiku is the embodiment of what a desktop OS could have been if it hadn’t taken the path of endless complication.

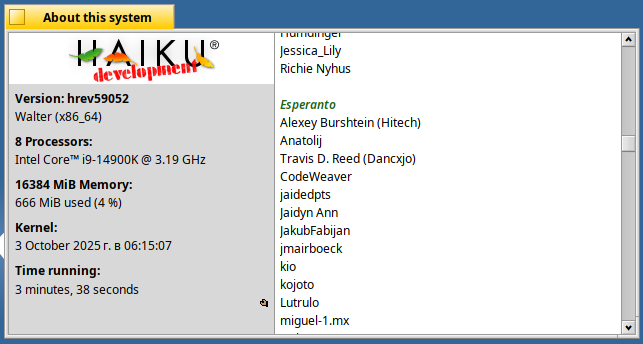

Ever since my first encounter with BeOS, I’ve stayed involved in its successor’s journey. Haiku is installed as the main OS on three of my computers. I’ve contributed by helping translate the interface into Esperanto, fixing small issues in the source code, and — most of all — developing native applications. For me, it’s both a playground for experimenting with its elegant API, a way to stay sharp with new technologies, and a chance to make life easier for myself and other users.

Today, Haiku remains a unique island of purity in a sea of bloated operating systems. It still boots instantly; installing it on a new drive is as simple as copying a folder. It needs no antivirus, (even though it has one), because its system files are mounted read-only. Haiku still uses BFS with full indexing and metadata, and its interface remains a model of clarity. There’s no telemetry, no forced updates, no sense of fighting your own machine. Haiku feels built for those who remember what computing paradise was like — when the human controlled the computer, not the other way around.

Yes, development is slow. But Haiku is a hobbyist OS — not a product, but a path. A path that preserves the spirit of BeOS, its aesthetics, and its engineering honesty. And as long as I can contribute even a little to keeping that path alive, I’ll stay with Haiku. Because it was Haiku that once taught me: simplicity is not a limitation — it’s a form of perfection.

The Haiku project site: haiku-os.org

Source code: haiku